Hopper continued to work at the Harvard Computation lab until 1949.1 Her next role was at Eckert–Mauchly Computer

Corporation, on the team that was creating UNIVAC I. At that time, computer programs were written in

a language called assembly, which used symbols and short mnemonics to represent the commands the

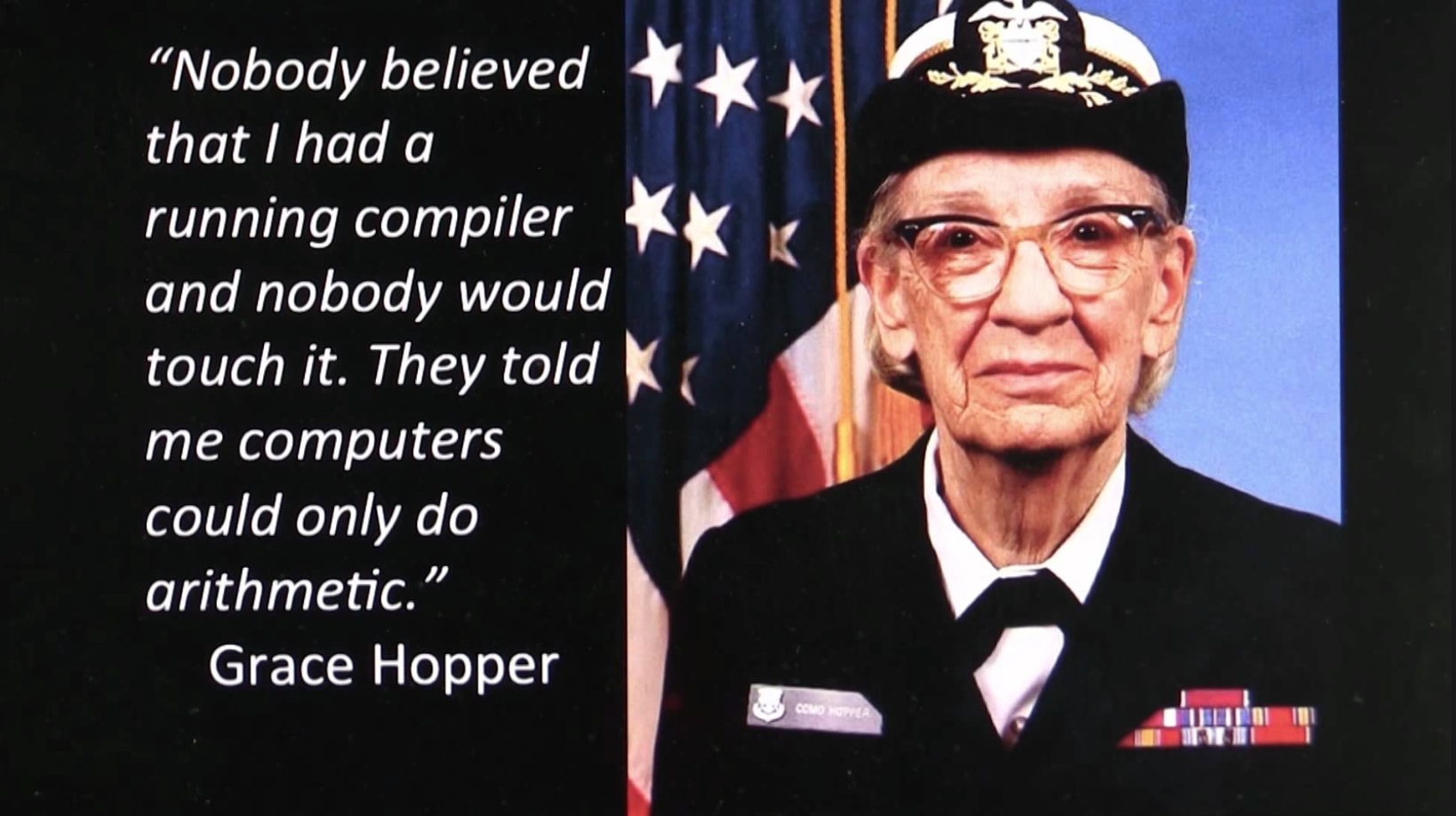

computer should perform. Grace Hopper envisioned a programming language based on English words that

could be run through some process that would translate it into a language the computer could

understand. This process came to be known as a "compiler", and the concept was at first dismissed by

her colleagues (see image at right). Hopper was undeterred and created the compiler anyway4, and even this working example

was ignored by her coworkers. Again, Hopper continued and her work went on to become the

COmmon Business-Oriented Language, or COBOL.4 COBOL allowed for using more intuitive language

and made the field more accessible.

Here is an example of COBOL code:

ADD 1 TO x

ADD 1, a, b TO x ROUNDED, y, z ROUNDED

ADD a, b TO c

ON SIZE ERROR

DISPLAY "Error"

END-ADD

ADD a TO b

NOT SIZE ERROR

DISPLAY "No error"

ON SIZE ERROR

DISPLAY "Error"

(This code was copied from the Wikipedia page on

COBOL) Even a non-programmer can get a sense of what is happening here.

Hopper continued to work to improve standard and practices within the Navy and the U.S. government

over the remainder of her professional career. Hopper first retired from the Navy Reserve in

1966.4 She was later recalled to

active duty and retired a few times (in 1971 and 1985). After retirement, Grace traveled widely and

lectured on her experiences and the history of computing. During this team, she is reported to have

said, "If you ask me what accomplishment I’m most proud of, the answer would be all the young people

I’ve trained over the years; that’s more important than writing the first compiler."1 Hopper believed

that the computer science field needed young people and their new ideas in order to keep moving

forward. Grace Hopper died of natural causes in 1992.2 She was 85 years

old.